A year ago, many of us were thrilled that our fellow-citizens joined us in rejecting 2011’s Issue Two; this year, we’re asking them to support a completely different Issue Two! We didn’t choose the timing or the issue numbers, but it’s no surprise that there’s a lot of confusion out there.

This year’s Issue Two is the Reapportionment Amendment. It was organized by Voters First, a coalition let by the League of Women Voters. The Ohio Education Association was one of the groups that supported the initiative, enacting a temporary dues increase to help support it. Early polls indicated that the idea of reforming Ohio’s reapportionment system was popular, but the details are complicated, and it’s harder to explain in 10-second sound bites. Recent attacks make the issue’s passage seem less likely.

I’m supporting Issue Two, and in this article I’ll explain why. But first, an acknowledgment of the main reason why it’s been a tough go: this is wonkish stuff, reforming a technological side of the system, Last year’s Issue Two was all about heroes and villains; this one is about computer models and the subtleties of an electoral system gone horribly wrong.

Let me acknowledge that in one respect, I’m like any Tea Partier you might know. Like members of the Tea Party, I’m deeply disturbed about the direction in which our country is going. But unlike them, one of my concerns is the extent to which the system rewards the wingnuts at the farthest extremes of the political spectrum. I’ve come to believe that Issue Two offers a chance to reform the system and bring some sanity to our political discourse.

And I’m feeling a bit wonkish myself, so let’s dig in.

What would Issue Two do?

Issue Two would replace the present system of reapportionment with a system in which officeholders and party officials and would have much less control over the outcome.

Why is this important?

Our ability to elect good legislators depends on having competitive races. The present system creates both Democratic and Republic districts that are practically unassailable.

What’s wrong with that?

It makes most Democratic and Republic incumbents virtually unbeatable and therefore takes away much of their incentive to represent their constituents.

How does it do that?

Typically, by carefully drawing district boundaries so that minority-party voters are “packed” into designated legislative districts and the majority party enjoys districts custom-designed to elect members of the party in power.

So this is about Republicans and Democrats?

To some degree. In statewide elections, Ohioans split close to 50-50 between the two main parties. But the legislative districts developed for the 2012 elections will almost certainly produce overwhelming Republican majorities in the Ohio General Assembly and the Ohio Congressional delegation: they were designed to.

However, it also means that many incumbent Democrats have districts drawn so that they can’t lose. That decreases their incentives to serve their constituents.

Whoever wins the elections–state Senators and Representatives, and US Representatives–won’t really need to meet with or listen to their constituents, because their districts have been designed to re-elect them.

In Columbus recently, I talked with an elected Democratic legislator who bemoaned what might happen to his “nice, comfortable” district is Issue Two passes. Since he’s been a reliable friend over the years, I didn’t tell him what I was thinking and should be obvious: he’d actually need to campaign in the new district.

I thought we were supposed to choose our representatives.

Voters are supposed to choose their representatives; however, under the present law the politicians chose their voters. Various media sources have identified the role of politicians in customizing district boundaries.

It can’t be that bad.

No? Let me illustrate with some congressional districts. The Voting Rights Act requires “minority opportunity districts.” Several media reports indicate that Ohio House Speaker Bill Batchelder suggested a minority Congressional district built like a barbell, with one cluster in Cleveland, another in Akron, and a narrow corridor between.

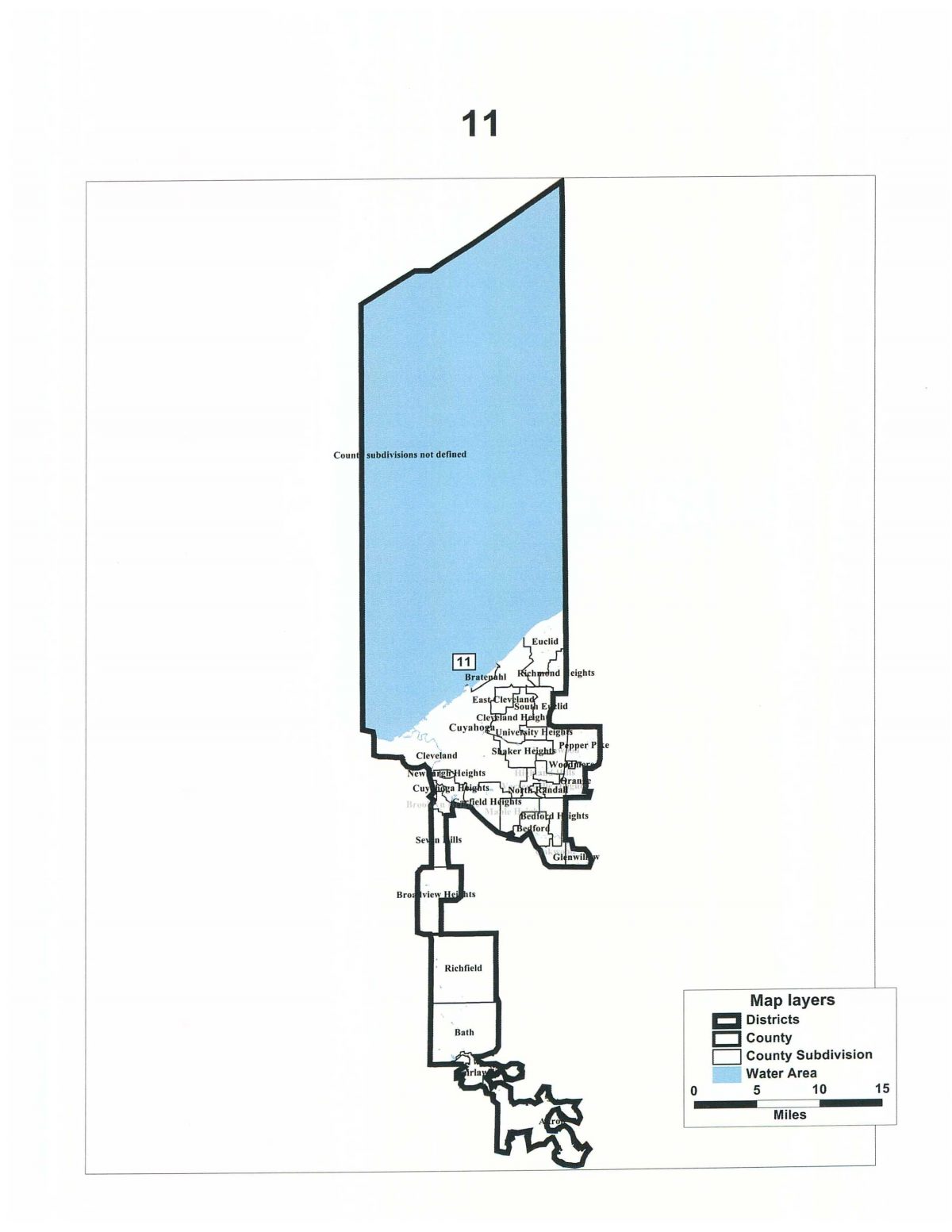

That packs Democrats into a safely Democratic district, but it also produces two monstrosities: first, there’s the black Democratic Congressional District 11 itself:

The design of that district allowed for the creation of an overwhelmingly white Republican

Congressional District 16, which wraps around

Congressional District 11 and the western tip of

Congressional District 13, which runs from Barberton to the Pennsylvania border.

Or take a look at

Congressional District 9, the widely-derided “Snake on the Lake,” which was designed to pit Democrats Marcy Kaptur and Dennis Kucinich against each other (and which it is virtually impossible to traverse on land):

Or Congressional District 4, which stretches 180 miles from Montezuma, in Mercer County (a few miles from Indiana), to Sheffield, in Lorain County.

Well, yes, these look pretty bad. But the critics are saying that Issue Two empowers unelected officials.

Right. And that’s because the present system allows elected officials to so clearly abuse their authority by creating districts that serve only partisan political purposes.

What will happen if Issue Two passes?

If Issue Two passes, a nonpartisan apportionment board will be charged with developing new districts to use beginning in the 2014 elections. Read more here.

The new criteria include community preservation, competitiveness, representational fairness, and

compactness. And if they do a bad job, the commission’s work can be challenged in court.

As a centrist Democrat, my own hope is that more competitive districts will encourage officials to work toward the political middle rather than pander to the most extreme elements of their parties. At the very least, the result will clearly be more rational districts and better representation. But my hope is more ambitious: I hope that better districts can lead to a less polarized political life, with candidates talking about real issues rather than the demonizing ads that we’re being subjected to during this campaign season.